Featured transcriber: Rebecca Cline

November 19, 2020

Rebecca Cline

It’s been a few months since our last ‘Featured transcriber’ interview, and we’re glad to pick up the series in this conversation with Boston-based pianist Rebecca Cline. Rebecca is a pro who plays all over the ‘Latin jazz’ scene — she’s even authored an instructional book on the subject. (More on the ‘Latin jazz’ term later.)

Photo by Martin Cohen.

Photo by Martin Cohen.

In this interview, Rebecca shares her wealth of knowledge and talks about what it was like to transition from her upbringing in strictly-notated music styles to those of improvisation. (Her Soundslice channel is a must-see.)

Soundslice: Rebecca, thank you for being the second pianist in our ‘Featured transcriber’ series. Your channel is extremely unique, and we’re glad to get to pick your brain.

Rebecca: It’s my pleasure to speak with you! I remember reading your interview with Fred Greene soon after I discovered your site. I’ve been following him ever since. I love his taste in music!

Soundslice: Having seen your channel, it seems like you and he have some overlapping tastes. Speaking of your channel, it says that you live in Boston. Are you from there? If not, how long have you been there?

Rebecca: I’ve been in Boston for just over twenty years. I’m originally from Athens, Georgia, but I spent several years in North Carolina, including the four years when I attended UNC-Chapel Hill. Immediately prior to Boston, I lived in Puerto Rico for about five years.

Soundslice: Oh, wow! ¿Hablas español?

Soundslice: Oh, wow! ¿Hablas español?

Rebecca: ¡Pues, claro que sí!

Soundslice: Fenomenal. To state the obvious, your channel features remarkable piano transcriptions from Latin jazz genres. Is there a scene for that music in Boston?

Rebecca: There is a Latin music scene in Boston, or there was, pre-Covid, of course. Over the last decade, most of my closest collaborators in the ‘Latin’ scene have moved away, and I have become busier playing jazz trio gigs. There is a new scene now, with different venues and younger players, although, happily, some of the veterans still perform. I always enjoy the opportunity to pop in and play for a dancing crowd.

Soundslice: Glad to hear that it is being continued. Were you always in that scene, or did you come into it at a later point in your musical development?

Rebecca: I pretty much only played music I could read, all the way through college, where I worked as an accompanist and did theatre gigs. But when I heard Michel Camilo’s 1988 trio release on Columbia right after I graduated, I knew what I had to do.

I moved to Puerto Rico with my keyboard and checked out the scene there nightly, while I worked out jazz fundamentals — like the blues form and basic voicings — in my apartment. With that rash move, I took a hard left from “I don’t play it if it’s not written down” to total immersion in the world of improvised music based on North American jazz and the rhythms and repertoire of Cuba and Puerto Rico. I couldn’t have asked for a better community in which to have taken those first steps into the abyss of the musical unforetold.

Soundslice: That’s an amazing, if not dramatic, development! When you were working on those jazz fundamentals on your own, did you have any resources to help? (Method books, etc.)

Rebecca: Yes. I studied Mark Levine’s

I also studied with a dedicated teacher named Jerry Michelsen, whom I met by approaching him after a set he played in one of the hotel lobbies in San Juan. He taught me three important skills: how to write a legible chart, the importance of transcribing, and the importance of compiling a book of tunes that I like to play. Those may seem like lofty goals for someone who was a total beginner like I was, but they served me well from the start, and I appreciate that Jerry took me seriously.

I also studied with a dedicated teacher named Jerry Michelsen, whom I met by approaching him after a set he played in one of the hotel lobbies in San Juan. He taught me three important skills: how to write a legible chart, the importance of transcribing, and the importance of compiling a book of tunes that I like to play. Those may seem like lofty goals for someone who was a total beginner like I was, but they served me well from the start, and I appreciate that Jerry took me seriously.

Soundslice: What fantastic advice. That last point I’ve heard repeated many times. ‘Play the songs you like to play,’ or better yet, ‘first learn the songs you know.’ So what happened when you get to Boston?

Rebecca: When I moved to Boston years later, I happened upon the ‘Latin’ scene right away and started working pretty regularly. I’m so grateful for that experience in Boston. It was a great hang. An invaluable opportunity to get comfortable with the standard repertoire and some of the stylistic nuances and performance practices that nobody tells you about.

Soundslice: Again, it’s just very cool to hear about that kind of musical pivot. Would you tell us more about what you pivoted from? What was your musical upbringing like?

Rebecca: I had a solid traditional music education, thanks to my first piano teacher, Ms. Sue Baughman. I was with her from the day I started at age six until my family moved to North Carolina when I was 11. She made sure I knew theory, like key signatures and time signatures, and how to notate music. I participated in yearly state-wide piano competitions, where you had to pass a theory test in order to qualify to place based on your performance. I remember feeling a lot of anxiety around competing, and she helped me deal with that too.

I am especially grateful to her for dedicating a portion of our weekly lessons to rhythmic exercises. We had syllables for all the subdivisions and she had me tap them out on the fall board while counting aloud. She also had me play the major scales with different rhythmic motifs and accents. That foundation provided me with a key to understanding complex rhythms later in life.

Soundslice: That’s rare and fortunate to have a teacher that would be so encouraging in the theory and rhythm department — she sounds like a special person. No question that the rhythmic exercises would come into play as you developed your skills in Latin jazz.

And if I may divert for a moment, for a music tradition that has so many genres and subgenres, I’ve always wondered about the nomenclature ‘Latin jazz’ — is it a label that musicians who are actually in that world — like you! — use?

Rebecca: Haha, well, it is definitely a fraught term. I dedicate four paragraphs in the introduction of my book to a disclaimer regarding the use of that term. I use it reluctantly, as a time saver, most often when communicating with non-musicians. With musicians, I usually specify the genre, such as guaguancó or cha-cha-chá. My friends in Puerto Rico have fun with the term, saying ‘Latin Yax’ instead.

Soundslice: Jaja. I figured an answer like that was coming. What’s your book?

Soundslice: Jaja. I figured an answer like that was coming. What’s your book?

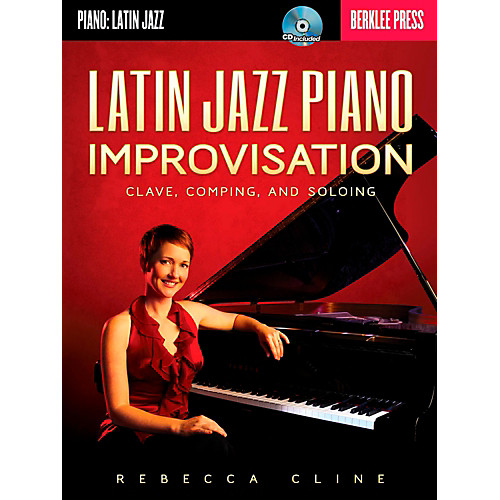

Rebecca: Latin Jazz Piano Improvisation: Clave, Comping, and Soloing, on Berklee Press, which is owned by Hal Leonard. I ended up writing my own musical examples for that book that aimed to capture the best of my favorite improvisers.

Soundslice: Very cool. Speaking of your favorite improvisors and transcribing, your channel has incredible snippets of rhythmic concepts found in this music. To someone like me — who doesn’t know much! — the rhythms are very complicated yet sound unforced. Lots of importance on the upbeats. Could you talk about a few of the key rhythmic concepts in this music?

Rebecca: Polyrhythms are used pervasively in improvised Cuban and Puerto Rican piano music. I currently have about 12 complete solo transcriptions published on Soundslice. From those pieces, and from many other solos that are not yet published, I’ve extracted short passages and labeled them according to the improvisational device featured in the excerpt. Rhythmic labels of excerpt slices include “triplet-based polyrhythm” and “montuno polyrhythm.”

Soundslice: How do you practice rhythmic concepts like these?

Rebecca: Shortly after I moved to Puerto Rico, I learned Eddie Palmieri’s solo on ”Bomba de Corazón.”

In that solo, he does that thing where you create a polyrhythm by playing the first three eighth notes of a montuno, and then you displace that figure over and over for about four to eight measures, adjusting pitches for changes in the harmony. In doing this, you are effectively juxtaposing the original pulse with the dotted quarter note pulse that is implied by the displacement of the three eighth notes. After I got that solo down, I recognized the device when it came up in other solos.

Soundslice: That’s fantastic.

Rebecca: One polyrhythmic device I am working on is one in which you take a four-note phrase that resembles part of a montuno, set it to quarter note triplets, and displace it for several bars. You can hear examples of this in the slices entitled “Descarga de Hoy” and “Tumbaíto Pa’ Tí.”

I’m working on this by playing along with a simple vamp I programed in a DAW that has a bass line for a two-measure progression in C minor — Imi IVmi V7 IVmi — and a live percussion track (clave, congas, and timbales) from the CD we recorded for my book. I make up simple four-note montuno-like motifs and try to displace them successfully, adjusting for the harmony, for a longer stretch each time, until I lose my place. The goal, of course, is to be able to displace a motif for as long as I want, with absolute confidence regarding my place within the progression.

Soundslice: That sounds like a fun way to learn something hard! We’re talking a lot about rhythm: What about harmony? Would you say one or the other is more crucial to this music?

Rebecca: Rhythm is certainly paramount. However, certain harmonic tropes also contribute to the identity of this music, such as I-IV-V-IV in major and minor tonalities, I-bVII-bVI-V7, for both major and minor tonalities and dominant seven vamps. These harmonic progressions all have brevity and simplicity in common — not by accident.

A seasoned bassist in Puerto Rico once told me that longer chord progressions are sometimes appropriate for certain sections in an arrangement, such as the verse. However, when it comes time to groove, the fewer chords the better. Two, or possibly three chords, max, are sufficient for a repetitive chorus section or a percussion solo.

A seasoned bassist in Puerto Rico once told me that longer chord progressions are sometimes appropriate for certain sections in an arrangement, such as the verse. However, when it comes time to groove, the fewer chords the better. Two, or possibly three chords, max, are sufficient for a repetitive chorus section or a percussion solo.

With so few chords to remember and/or find on the instrument, the musician can devote more bandwidth to the time placement and the sound of the notes. I strive for consistency in time feel and a percussive, precise articulation in these groove scenarios.

Soundslice: Two to three chords max. I love that.

If you could send yourself a message back in time, what 5 albums would you recommend to the Rebecca who was just starting to learn this music in Puerto Rico?

Rebecca:

- Concepts in Unity, by Grupo Folklórico Y Experimental Nuevayorquino

- Rican-Struction by Ray Barretto

- Piano Con Moña (possibly reissued under another title) by Pedro ‘Peruchín’ Jústiz

- Nueva Visión by Emiliano Salvador

- Recuerdos de Habana, by Bebo Valdés

Soundslice: Thank you for that listening advice! One last thing we like to ask in each interview: Do you have a dream Soundslice feature request? It could be anything from a new transcription tool to different piano sounds…

Rebecca: I would love to see more sub-genres of ‘Latin jazz’ available in the pull-down menu of styles. I’ve also thought it might be helpful to tag a slice by the country of the performer’s origin, such as Cuba, Puerto Rico, or Colombia. I would not like to lose the style of ‘Latin jazz,’ because sometimes, when an arrangement encompasses music from many sources, ‘Latin jazz’ can be the most apt description.

Soundslice: That tagging of a performer’s origin is such a cool idea. It’d be neat to imagine all of those transcriptions plotted on a map. As to adding those sub-genres, we can do that easy! I’ll be following up for your expertise. Anything else?

Rebecca: I would also enjoy having the same organizational capability on my channel’s public face. For example, I have my slices organized in folders, and I believe the public sees slices in reverse chronological order. If viewers were aware of how the various slices are related to each other, that might increase their engagement with the channel. I don’t know if folders are the way to go on the public view, but perhaps slices could be tagged such that the viewer could select other slices with the same tag.

Soundslice: That makes total sense — yes, as it is, the channel posts show in reversal chronological order and don’t reveal any deeper organization. We’ll have a think on that.

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us, Rebecca! We really appreciate your expertise and are grateful that you’ve contributed so many great transcriptions to the community!

Rebecca: And I would like to thank you and your partners at Soundslice for creating this fantastic tool for experiencing music notation and performance simultaneously! About five years ago, I spent months trying to achieve a similar result by recording screencasts of notation software playback, then syncing up the audio with the screencasts in a movie editing program. That took hours, and the result was fixed, without the ability to slow down the tempo, loop sections, or view the notes on a virtual keyboard. It’s amazing to me how immediate and effortless the process is on Soundslice. Keep up the great work!